It’s pretty simple really: Don’t drink alcohol.

OK, there has to be a Plan B because if you don’t drink beer then there is little point to Realbeer.com.

Nicholas Plagman offers some basic advice: Drink water, take a B complex.

It’s pretty simple really: Don’t drink alcohol.

OK, there has to be a Plan B because if you don’t drink beer then there is little point to Realbeer.com.

Nicholas Plagman offers some basic advice: Drink water, take a B complex.

Yes, it’s time to polish that beer resume. The hunt is on for the 2007 Beerdrinker of the Year.

Highlights from the press release:

Wynkoop Brewing Company – Denver’s first brewpub and one of America’s most respected microbrewing establishments – is now conducting its search for the 2007 Beerdrinker of the Year.

The annual contest seeks and honors the most passionate, knowledgeable beer lover in the United States. Wynkoop is now seeking “beer resumes†from the nation’s most beer-minded men and women.

Resumes must include each entrant’s beerdrinking philosophy and details highlighting their passion for beer. Resumes should provide evidence of the entrant’s understanding of beer, its history, and its importance to civilization.

Resumes must be received by Wynkoop by no later than December 31, 2006.

Resumes for the Beerdrinker of the Year award are reviewed by a collection of the nation’s beer experts, beer journalists and previous Beerdrinker winners. The top three entrants will be flown to Wynkoop Brewing Company (at Wynkoop’s expense) for the Beerdrinker of the Year finals on February 24, 2007.

What you really need to know:

• Resumes must include the entrant’s personal philosophy of beerdrinking.

• Do not enter if you are currently employed in the brewing industry.

• Resumes with both rich beeriness and humor are welcomed.

• Beer resumes cannot exceed three 8 1â„2″ x 11″ pages and must be written in a 12-point or larger font.

• Resumes must include the name of the entrant’s home brewpub or beer bar, and their T-shirt size.

• Resumes created in Word can be emailed to Wynkoop Brewing Company (sent as an email attachment) to [email protected].

Beerdrinker of the Year resumes can be sent by mail to:

The Beerdrinker of the Year

Wynkoop Brewing Company

1634 Eighteenth Street

Denver, Colorado 80202

Here is the final installment of your conversation with Maureen Ogle, author of the Ambitious Brew. The first two: Part one ~ Part two

7. How did beer change for you in the course of researching and writing the book?

The short answer is that when I started the book, my only experience with beer was back in college (dime-beer hour at the Vine in Iowa City). And for most of the book, beer remained an abstraction, just something that had earned a fortune for all those dead people I was writing about.

The short answer is that when I started the book, my only experience with beer was back in college (dime-beer hour at the Vine in Iowa City). And for most of the book, beer remained an abstraction, just something that had earned a fortune for all those dead people I was writing about.

But then I began interviewing the living, and everything changed. The men and women I talked to – Jim Koch, Byron Burch, Nancy Vineyard, Dick Yuengling, and others – were lively, intelligent, fully engaged with the world around them – and utterly passionate about beer.

That got my attention. What was it about beer, I wondered, that inspired someone like Fritz Maytag, for example, who had the brains and ambition to do anything, to fashion a career out of beer? So one day I went to the store and bought some beer (trying to find ones brewed by people I had interviewed) and began tasting. And thinking about what I was tasting, and marveling at the color of these beers (there are few things more beautiful than a fine beer!) I was hooked. Beer, I discovered, was every bit as complex and interesting as wine, perhaps more so. And it tasted as good, if not better, with food.

Do I qualify now as a beer connoisseur? No. No one’s ever gonna ask me to supervise a beer tasting or ask me to judge a competition. But I admire fine beer and I’ve learned enough about beer to know what I like and don’t like. And perhaps most important, I know enough to respect the skill and art required to fashion a fine beer.

Because of the way our “printing press” works we can also include the longer answer:

Brewing is one of the most heavily regulated (and taxed) industries in the United States: federal, state, and local laws determine when and where beer can be sold, who can buy it, and even the wording and content of labels.

That’s not always been the case. The late nineteenth century may not have been the golden age of the beer itself (today we enjoy more variety and the quality of contemporary beers typically surpasses that of ones made a century ago), but it was a halcyon age of few regulations and low taxes.

Congress only levied a tax on beer in 1862 in order to generate revenue to fight the war against the Confederacy. After that taxes drifted upward slowly and fitfully: brewers were well-organized and had plenty of friends in high places. Moreover, selling beer was easier than at any other time in American history. Back in the near-utopian nineteenth century, brewers were allowed to own saloons. Most owned dozens if not hundreds, funneling their lagers directly from brewery to their “tied†taverns.

But then came prohibition, the short-lived experiment in sobriety that fundamentally altered the way brewers operate.

Prohibition was the brainchild of the Anti-Saloon League, a group of social activists who believed alcohol was impeding national progress. Their original goal was simple and logical: shut down the saloons. Close the saloons and brewers would have no place to sell their wares, and they’d be forced to close their own doors.

Between 1895 and the onset of World War I, that plan worked, as one precinct and town, one county and one state after another voted itself “dry.†Even places that remained “wet†imposed new barriers to the brewers’ way of life, levying enormous license fees on saloonkeepers and new taxes on brewers, and ordering saloons shut on Sunday,

Beer came back in 1933, but the good old days did not. The laws that legalized beer also surrounded brewing with a jungle of regulations and restrictions: No more “tied†houses. Every word of every beer label had to be approved, and at multiple levels: what a state regulator might allow on a label, a city licensing board might deny. Taxes soared, crippling marginal beermakers and driving them out of business.

And so it continues today: brewing is a fiercely competitive business, but behind the headlines of Anheuser-Busch duking it out with Miller lies another tale, as brewers struggle to comply with federal laws; with fifty sets of licensing and sales laws in the fifty states; and thousands of other regulations imposed by counties and municipalities. And the taxes go up and up and up ….

Making beer? It’s never been harder than it is today. All the more reason to admire and appreciate those brave souls who enter the business every day, men and women whose passion for fine beer outweighs the burden of regulations that will shape their working lives.

We recently asked Maureen Ogle, author of the Ambitious Brew, a series of questions. This is the second in a series of three posts with her answers. (Part one.)

4. How is this book similar/different than the previous two? What’s next?

4. How is this book similar/different than the previous two? What’s next?

Ambitious Brew was much more ambitious (no pun intended) than my two previous books. The Key West book covers a longer period of time, but its scope is much narrower. The plumbing book, my “tenure†book, was written for an academic audience and so it had to follow a certain formula.

But with the beer book, I could let my historical creativity roam and the subject itself was so rich and so complex that the project took on a life of its own. Most of the time, the material dictated and I just tried to hang on for the ride.

Also, the book taught me a great deal about myself and about how to “do†history. I think (I hope!) I’m a much better historian now. I believe, anyway, that I rose to the challenge posed by beer, a fascinating, complex beverage with an equally fascinating, complex history.

Having said that, I should also note that my three books share certain attributes. First, I’m fascinated with the way in which American values — our “culture†— shape our material world, whether that be plumbing, cities, or food. Along the way, I’m drawn to the everyday “stuff†that we take for granted and to the lives of men and women whose drive and ambition compel them to create something from nothing.

The plumbing book, for example, examined the way in which the values of the 1840s and 1850s shaped the form and function of household water supply and waste systems. Not ideas about public health or germs, as one might expect, but a desire on the part of a newly emerging (and somewhat insecure) middle class to promote progress and individual initiative. The Key West book chronicles the way in which a handful of ambitious dreamers transformed that infertile island into a profitable venture.

Ambitious Brew examines an everyday staple by looking at the nineteenth-century German emigrés who abandoned their traditional lager and invented a new world version that appealed to the American palate. Their success transformed beer and brewing from a local and small-scale enterprise into one of the nation’s largest industries. The book also records the history of the late twentieth century visionaries who challenged corporate complacency, built “micro†breweries from scrap metal, and reinvented the industry.

I’ve already started a new book: a history of meat in America, from the great pork “factories†along the Ohio River in the 1820s, to the “organic†ranchers of the 1970s. I’m fascinated by the production and consumption of food and drink – perhaps the most revealing of all human activities – so I expect to have a grand time with this project.

5. Pick the three misconceptions you’d most like to set straight.

I think the biggest misconception is that in the 1950s, brewers dumped “adjuncts†such as corn and rice to their beer into their brewvats and did so in order to reduce production costs; to make a cheap beer to sell at a high price. Not so. Brewers began adding corn and rice to their beers in the 1860s and 1870s because non-German-Americans wouldn’t drink a heavy all-malt beer. They wanted a lighter-bodied, more effervescent beer, and the only way to make one using American barley was by adding other grains to absorb the excess proteins. Moreover, those adjunct-based beers were expensive: in the 1870s, a barrel of adjunct-based beer cost about two dollars more to make than an all-malt beer.

Another misconception is that after World War II, brewery numbers plunged as the rapacious giant Anheuser-Busch drove smaller brewers out of business. Again, not so. Between 1945 and the early 1960s, beer consumption declined or remained stagnant. Americans weren’t interested in drinking beer (they either didn’t drink at all, thanks to the prohibitionists, or they preferred hard liquor) and every brewer struggled to stay afloat.

Were the big guys more likely to survive? Sure, because they had the money to invest in things like television advertising, which was a new medium in the 1950s, and because they were able to exploit national markets more easily than were smaller brewers. But the period from 1945 to c. 1961 (when the first wave of baby boomers hit legal drinking age) was the darkest period in American brewing, and no one had an easy time of things.

Third, when I started the book, I assumed that Prohibition began in 1920. It didn’t. The Anti-Saloon League, the lobbying group that spearheaded the prohibition movement, set up shop in 1895 with a plan to drive saloons out of business. They succeeded: by 1910, half of all Americans already lived under some form of prohibition, either local or state. Brewers failed to organize a resistance movement, and were unable to fend off this piecemeal destruction. By the time the Eighteenth Amendment and the Volstead Act went into effect in January 1920, brewers had already been out of business for over a year.

Fourth (I know you only asked for three…..): Pabst Blue Ribbon labels still carry a medallion indicating that the beer was chosen as “America’s Best†at the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893. It wasn’t! (See Chapter Three . . .)

6. Which three principals in the book (dead or alive) would you most like to have a beer with?

Oh, boy, that’s tough. Adolphus Busch and Frederick Pabst for certain. (Although I feel as though I’ve already met them: For about three months, I dreamed about them every night. We ate dinner together, walked through their breweries, took carriage rides. . . . Sounds odd, but that’s what happens to writers when we spend months on end with people, dead or alive!)

Who else? Phillip Best, the man who founded what became Pabst Brewing (Frederick Pabst married his daughter). I’d love to know if he really rolled dice to determine who got the brewery, himself or his brother.

Truth is, I’d love to meet everyone. I’ve met most of the living brewers who are featured in the book, but it would grand to sit down and talk to everyone else who landed on my pages!

Tomorrow: How did beer change for you in the course of researching and writing the book?

We recently asked Maureen Ogle, author of the Ambitious Brew, a series of questions. The e-mail conversation turned out to be long enough that we’ll post her answers to seven questions in three parts.

First, a bit about the book. It is ambitious itself, seeking to tell the history of American beer in a different way – thus passing on Colonial history we’ve read about many times over – and starting with . . . well, that’s our first question.

First, a bit about the book. It is ambitious itself, seeking to tell the history of American beer in a different way – thus passing on Colonial history we’ve read about many times over – and starting with . . . well, that’s our first question.

Those interested mostly in the American beer revolution will want to turn toward the back of the book, because Ogle tracked down the elusive Jack McAuliffe. But you should start from the beginning to understand the choices financially successful brewers made along the way, decisions that by the second half the twentieth century left America with one dominant beer style, the light lager.

Let’s get started.

1. Why start in 1840?

From the perspective of someone in the brewing industry, a more logical place to start the book might have been, say, 1620 and the first colonists. But I’m a historian, not a beermaker. So I was looking for the historically significant story. And that tale – the moment when beer surpassed spirits in popularity and an industry emerged – began with the vast wave of German immigration that began in the 1840s.

Had a thriving brewing industry existed in the colonial period, the book would have opened in, say, the eighteenth century. But there wasn’t and so it doesn’t. That’s not to say there wasn’t any beer. Most people brewed at home, making a low-alcohol beer that functioned as the equivalent of our safe tap water. But that’s not a particularly interesting story! In the colonial era, the story of alcohol – the historically significant story – is of rum. But even after the revolution had ended, spirits were more important than beer: In 1820, there were some 14,000 distilleries, but a mere two hundred breweries. That alone tells me where beer stood in the hearts of minds of the American people!

2. How did your academic training influence your decision to pick the topic of beer? You write the book totally changed from start to finish. How?

First I experienced my “wham!†moment (when I saw a beer truck and thought “Hmmm….wonder if anyone has written about beer.â€) But then the historian in me took over and asked two crucial questions:

First, were there any other histories of beer out there? If there a zillion of them, then this project was a non-starter.

But the answer was no; there weren’t any other beer histories of the sort my brain was starting to fashion. So the second question kicked in: Did that mean there was no “story†to tell? Was the history of beer worth several years of my life?

Off to the library, where I devoted a week or so rooting around in the few books written about beer to see if I could find a bare-bones outline of beer’s American history and, from that, determine if I could shape it into something worthwhile.

Next, I spent nearly a year writing a proposal that described the book (this is the document that an agent uses to sell the book idea to a publisher). But writing a proposal of an imagined book, and writing a book based on months and months of in-depth research are two different things. My original proposal outlined a particular narrative, all based on what I thought I’d find once I began the research. But, as always happens, the research itself turned up one surprise after another and led me off in directions I could not have imagined.

3. What was hardest in doing research? Easiest: Most frustrating as a historian?

Hands down, the first three chapters, which cover 1844 to Prohibition, were the toughest. I crawled through a good many of the proverbial haystacks hunting for materials, facts, and details. Most of the nineteenth century breweries are gone, and so are their records. The largest repositories of archival material are at Miller and Anheuser-Busch, and both refused to allow me access. (They weren’t being jerks; most corporations would be reluctant to let an outsider in.)

Had it not been for nineteenth-century newspapers (especially the Milwaukee Sentinel and the New York Times, both of which are indexed) and trade journals such as Western Brewer and American Brewer, I’m not sure I could have written those first three chapters. It took me as long to complete them as the next five chapters combined.

Things became much easier once I hit the twentieth century. Prohibition is well-documented, as is the brewers’ response to it. And for post-repeal brewing, I had all the magazines, trade journals, and newspapers I could handle. Indeed, toward the end, I almost had too much information. Plus, for the first time I was interviewing living people, and they all had plenty to say!

Certainly the most frustrating part of the whole gig was A-B’s refusal to cooperate. The company historian taunted me with the fact that his vault contained hundreds and hundreds of letters written by Adolphus Busch as well as thousands of other company documents as well. I don’t even want to think about what’s in there and what I might have been able to do with it.

Tomorrow: How this book is different than non-beer histories she has written, and setting misconceptions straight.

The Brewers Association recognized the work of three journalists for outstanding coverage of the flavor and diversity of American craft beer. The awards, sponsored by Rogue Ales and Samuel Adams were given to Don Russell for his Joe Sixpack Beer Reporter column in the Philadelphia Daily News, Carolyn Smagalski for work that appeared in the Beer & Brewing section of BellaOnline and Tony Galea for an article in Yankee Brew News.

The awards were handed out at the Great American Beer Festival.

“As craft beer continues to grow, consumers look to the media to explain and explore the diverse culture of American beer,†said Ray Daniels, director of Craft Beer Marketing for the Brewers Association. “Thanks to Rogue Ales and Samuel Adams, we are able to both recognize and reward the work that these journalists have done.â€

The Great American Beer Festival celebrates its 25th anniversary beginning tomorrow in Denver.

Eight breweries have been present at all 25. Can you name them? (Answer tomorrow.)

The Independent in London has Michael Jackson write their obituary for John Young, long te venerable leader of London’s historic brewery. It should be read in its entirety but in case you need a nudge, here’s an excerpt.

He has been described, inadequately, as an eccentric. People thus identified are usually bores. Young was never boring. Barking, perhaps. If the rest of the world were sane, he would indeed have to be judged mad.

He was also a giant, which Jackson’s tribute makes clear.

The National Beer Wholesalers Association (NBWA) this week honored Bob Lachky of Anheuser-Busch for his efforts to promote beer and the role distributors play in the marketplace, with its Industry Service Award presented at NBWA’s annual meeting in Orlando, Florida. The award recognizes individuals who have made a contribution that enhances the malt beverage industry.

Lachky has spearheaded the “Here’s To Beer†campaign, which is ongoing.

25th Great American Beer Festival, 14 days and counting . . .

The GABF has announced a new feature – Inside the Brewers Studio, patterned after the television show “Inside the Actor’s Studio.” The shows will be presented in the Brewers Studio Pavilion at the center of the festival floor. Tom Dalldorf of Celebrator Beer News moderates each of them.

Thursday, September 28, 7-7:30 p.m.

Vinnie and Natalie Cilurzo of Russian River Brewing Co. and Matt Brynildson of Firestone Walker Brewing Co. discuss their brewing adventures in Northern and Central California.

Thursday, September 28, 8-8:30 p.m.

Rob Tod of Allagash Brewing Co., Adam Avery of Avery Brewing Co., Sam Calagione of Dogfish Head Craft Brewery, Tomme Arthur of Port Brewing Co. and Vinnie Cilurzo of Russian River Brewing Co. all traveled to Belgium together in March, even taking along their own beer for Belgians to sample. They’ll share stories about the trip.

Friday, September 29, 7–7:30 p.m.

Garrett Oliver and Mitch Steele are both veterans of American brewing. Oliver is the brewmaster at Brooklyn Brewery and author of The Brewmaster’s Table. Steele recently became brewmaster of Stone Brewing Co. after brewing more than 10 years for Anheuser-Busch. They’ll interview each other about their careers, “talk some East/West smack”, and answer questions.

Friday, September 29, 8–8:30 p.m.

Charlie Papazian, founder of the GABF and president of the Brewers Association, and Boston Beer Co. founder Jim Koch will share stories about the last 25 years of craft beer.

The American Breweriana Association has given Gregg Smith its 2006 “Excellence in Literature†award for his latest book, titled “A Beer History: A Day at a Time Through the Year.â€

Caledonian brewery chief Stephen Crawley said the Great British Beer Festival should be moved to winter.

Crawley also suggested that brewers need to be involved more directly in organizing the event. The Campaign for Real Ale runs GBBF and CAMRA chief Mike Benner was quick to replay to Crawley.

“The question is irrelevant because we had 66,000 people attend this year – 20,000 more than last year,” Benner said. “By holding the festival in August we attract alot of tourists and we have no problems keeping the beer cool.”

Imagine the Wall Street Journal with color pictures (wait, they do that from time to time) to accompany its “Fresh Hops” story of last week.

Then you’ve got Jay Brooks’ story and photos from the Russian River/Moonlight Brewing hop harvest on Monday.

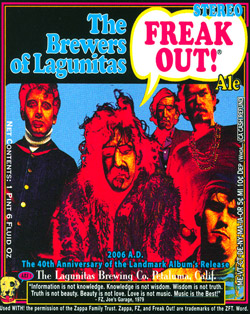

First Thelonious Monk, now Frank Zappa.

First Thelonious Monk, now Frank Zappa.

Compared to the heat Miller Brewing has drawn for using famous rock ‘n’ roll artists on a series of cans, it looks like small breweries – in this case both from Northern California – are on to something.

Lagnunitas Brewing Co. began shipping Freak Out! Ale in 22-ounce bottles earlier this month “in celebration of the 40th anniversary of the release of the first album by Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention.”

Lagunitas founder Tony Magee obtained the permission of the Zappa Family Trust to use the original album art as the bottle label. He plans to do an entire series commemorating the release of Zappa albums. So look for “Absolutely Free” next summer.

Freak Out! Ale is a beer of substance (7.3% abv) but – thank goodness – is not as demanding as Zappas’ double album. It has plenty of hop character – citrusy, resiny, gritty flavors and solid bitterness – to balance hefty malt sweetness (fruit and caramel).

Lagunitas also announced that its Imperial Red Ale (also not for sissies), previously sold only in 22-ounce bottles, is available in six-packs of 12-ounce bottles.

Two Colorado breweries have already taken steps to make the 25th anniversary celebration of the Great American Beer Festival a bit more special. Perhaps there’ll be news of more in coming weeks.

You can already find special cans of Dale’s Pale Ale in many of the 13 states that Oskar Blues (in Lyons, just up the road from Boulder) sells its beer. The cans feature the GABF logo and information on the festival, scheduled for Sept. 28-30 in Denver.

The Brewers Association and Boulder Beer teamed up to produce a beer commemorating the 25th GABF. Boulder Beer also brewed a special high gravity ale to celebrate the inaugural GABF in 1982.

Boulder Beer was one of the original 22 breweries at the first GABF and has been a participant every year since.

Boulder will roll out its “GABF 25th Year Beer” in 11 states in early September – and, of course it will be available at the festival. it will first be served at Boulder Beer’s 27th anniversary party, The Goatshed Revival, Aug. 26 from 1 – 8 p.m. The Goatshed Revival is an annual outdoor celebration with proceeds benefiting the local Habitat for Humanity.